Poker and Software Engineering

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The last editorial we did was 10 Philosophies for Engineers. Listeners enjoyed that episode, so we decided to do another.

10 Philosophies was a collection of beliefs I have about the software engineering industry, and how we can find fulfillment in our work as engineers. The philosophies that I discussed were rooted in my experiences working as a computer science student and as an engineer at several different companies.

Before writing any lines of code, I played poker competitively for five years, from the age of 15-20. This was a formative experience. Playing poker changed my perspective on money, risk, and statistics.

It has been 7 years since I stopped playing poker full time, but the lessons of the game are still with me.

In this editorial, I will discuss some beliefs I have that relate to both poker and software engineering.

As with the 10 Philosophies episode, these beliefs my own opinions. If you disagree with them, I would love to know why. At Software Engineering Daily we actually want to know any thoughts you have on our content.

We make content for our listeners and our readers. Please tell us how we can improve by emailing us, or by filling out the listener survey.

As a poker player becomes a software engineer, certain trends about human-computer interaction become apparent:

- human poker players will lose to computers in the near future

- every field is plagued by the madness of crowds

- emotional labor is a competitive advantage

- creativity and autonomy are necessary for success

This post explores each of these trends, explaining why these trends are important to poker players, software engineers, and everyone else.

Automated Games

In 2008, poker was the perfect sport for human-computer symbiosis. What Tyler Cowen said about freestyle chess also applied to poker:

Even very strong computers don’t have that meta-rational sense of when things are ambiguous. Today, the human-plus-machine teams are better than machines by themselves. It shows how there may always be room for a human element.

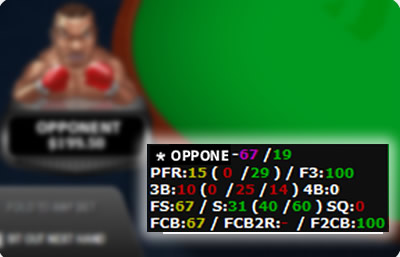

In poker, a human with a statistical “heads-up” display can make decisions that are more mathematically justified than a human without such a tool.

Heads-up displays create the poker version of “human-plus-machine teams”.

One thesis of Average is Over is that a human will only be employable in the future by finding a career where human reasoning provides defensible value to the problem solving process of a computer.

If the human’s responsibilities are not defensible, the human will beobviated.

In a subsequent blog post, Cowen addresses the “flip” that can occur when a computational problem no longer requires human assistance:

Fairly soon, the computer programs might be good enough that adding the human to the computer doesn’t bring any advantage. (That’s been the case in checkers for some while, as that game is fully solved.)

Think about why such a flip might be in the works, even though chess is far from fully solved.

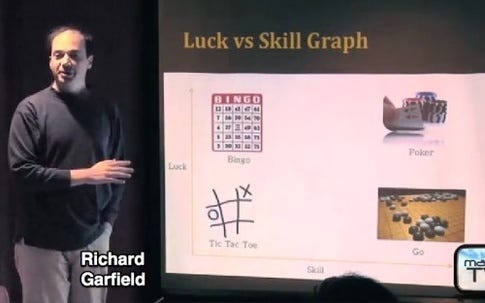

Poker players have been increasingly defeated by machines for the past 10 years. It is no surprise that Google’s AlphaGo has defeated human champion Lee Sedol.

If Google decided to beat humans at poker, it would be a trivial exercise for the researchers.

Poker seems different than Go or Chess, since there is nondeterminism. You start with two cards, but you don’t know how the board will develop. It would seem that fate is in control, unlike Go and Chess, which have no random elements.

With just 4 suits and 13 ranks, a poker game has a trivial branching factor. The nondeterminism is so minimal for a computer to plan around that it is effectively deterministic.

Imagine if AlphaGo had to learn to play a version of Go with the following rule: at the beginning of each turn, flip a coin. If you lose the flip, you don’t get to move. Adjusting to this rule would be trivial. That is the magnitude of nondeterminism within poker.

Poker, Chess, and Go have small decision spaces. The rules never change, the game pieces never change, there is minimal nondeterminism.

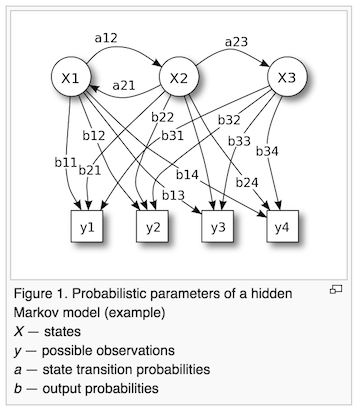

A computer can assess a hand of poker as it would a hidden Markov model, but it will take work on par with the AlphaGo team for a computer to be trained to build a model accurately.

The job of a professional poker player has been a bad long-term choice for a human to pursue for more than a decade, because it is vulnerable to automation.

Games like Go, Poker, and Chess can be automated with machine learning techniques we understand today. The rules, game piece schema, and objectives are easy to define, so these games are ripe for supervised learningand reinforcement learning.

Yann LeCun protested against the hype around the AlphaGo victory:

As I’ve said in previous statements: most of human and animal learning is unsupervised learning. If intelligence was a cake, unsupervised learning would be the cake, supervised learning would be the icing on the cake, and reinforcement learning would be the cherry on the cake. We know how to make the icing and the cherry, but we don’t know how to make the cake.

We need to solve the unsupervised learning problem before we can even think of getting to true AI. And that’s just an obstacle we know about. What about all the ones we don’t know about?

Poker is vulnerable to the same supervised learning and reinforcement learning techniques that allowed AlphaGo to beat Lee Sedol in Go.

Supervised learning is the machine learning task of inferring a function from labeled training data. Billions of hand histories exist for a poker bot to train on. These hand histories are short and well-schematized, perfect for consumption by an automaton.

Reinforcement learning is learning by interacting with an environment. Poker bots can test and parallelize their strategies across the thousands of free or cheap poker games on the internet. The reward signal of a strategy can be defined as profit over a given time horizon.

Today, the surviving human professionals cannibalize each other. Before long, even the best of these players will be losing their money to bots.

Games that cannot be easily solved with simple supervised learning and reinforcement learning will not be automated in the near future. Examples include Magic: the Gathering, Sim City, Minecraft, and Dungeons and Dragons.

Features of these games include:

- large branching factors at the points of nondeterminism

- a large game piece corpus with a game piece schema that is hard to normalize

- non-negative sum nature

- subjective player goals

- widely varying end-game states and win conditions

Rules, success, and failure are easy to define in Go, Chess, and Poker.

In contrast, it is difficult to explain what makes an ideal Minecraft player. Different Minecraft players have different goals and win conditions. We have no way to supervise a computer to succeed at Minecraft, or to reward a computer for its desirable Minecraft behavior.

Poker has 52 game piece types, Chess has 6, and Go has 1. Magic: the Gathering has 16,000+ unique cards. We don’t know how to teach a computer to understand the complex strategic relationships among these 16,000 different card types.

Dungeons and Dragons is cooperative, positive sum, highly random, and oriented around subjective player goals. A computer won’t rival the creative, utilitarian humanism of a talented dungeon master any time soon, because we don’t have a good way to codify the traits of a successful game of Dungeons and Dragons.

As humans, these are the games we should be studying and celebrating.

AlphaGo proves that Go is just another routine that can be automated, like fast food preparation or truck driving.

Rather than spending our time on Chess, Go, or Poker, human time is better spent playing games that mirror activities which a computer has trouble with.

Choosing a career as a professional poker player today is like choosing to be an Uber driver or an Amazon warehouse worker: you are waiting to be automated away.

Madness of Crowds

In both poker and software, market participants confuse technical analysiswith fundamental analysis.

Technical analysis is a security analysis methodology for forecasting the direction of prices through the study of past market data, primarily price and volume.

Contrasting with technical analysis is fundamental analysis, the study ofeconomic factors that influence the way investors price financial markets. Technical analysis holds that prices already reflect all the underlying fundamental factors.

Pure technical analysts believe dogmatically in the wisdom of the crowds.

Technical analysts believe there are no secrets, and that all human knowledge about the future is factored into the crowd’s evaluation of the present.

Reasoning about markets using first principles can lead to decisions that differ from the wisdom of the crowds. This is a form of fundamental analysis.

In 2003, an accountant turned amateur poker player named Chris Moneymaker won the World Series of Poker. This coincided with ESPN’s increase in video coverage of the event. People started going to restaurants to watch poker like it was the Super Bowl.

As poker became popular across the world, many unskilled players began playing the game.

In 2004, any computer-savvy teenager could learn to play poker and take money from the numerous unskilled Americans who were trying to become the next Chris Moneymaker.

There was a wealth of information about how to win at poker online, and it didn’t require much effort to study enough of that information to be successful.

For teenagers who were good at online games, it was a gold rush. Teenagers who had skills from games like StarCraft and Magic Online quickly learned poker and began obliterating the unskilled amateurs.

In 2006 the online poker bubble sprung a leak with the passage of the UIGEA. The Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006 made it difficult for amateur players to fund their online poker accounts with credit cards.

In 2008 the global economy collapsed, further reducing the number of casual gamblers on the Internet.

In 2011 Black Friday occurred and it was discovered that Full Tilt Poker was a Ponzi scheme.

Since 2006, online poker has gotten increasingly difficult, and an ever growing number of poker players have complained about the macro environment of poker.

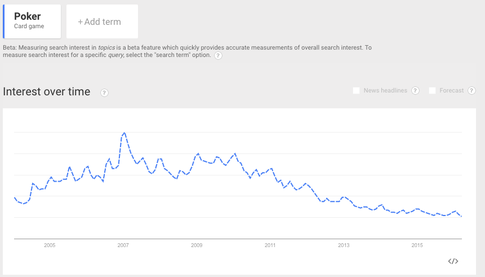

Google Trends says that poker popularity has dropped by 80% following the passage of UIGEA in late 2006.

Since 2006, poker players have been saying: “there are no more weak amateurs. We are all fighting each other, and because we all have the same strategies, we are essentially flipping coins against each other. Poker has become a game of complete variance.”

None of this matters to Dan Cates, Mike McDonald, and Patrik Antonius. Their strategy is sufficiently better than their opposition that they have afundamental opportunity. They have continued to win despite a steep increase in competition.

Average poker players who are not innovative nor resilient viewed the events of 2006–2011 as fundamental threats to their viability as professional poker players, when in fact these problems were technical in nature.

The details of the market changed, but the fundamental opportunity remained: the best players still have enough of an edge to make a great living playing poker.

When investors and entrepreneurs talk about a “bubble” in Silicon Valley, they are talking about a technical bubble. Not a fundamental bubble.

Cheap cloud computing, mobile phones, emerging markets of China and India, social networks, Docker, Bitcoin, supply chain economics, drones, fintech, virtual reality: these are fundamental opportunities with huge growth potential.

When investors and entrepreneurs talk about how “Winter Is Coming”, what are the cited underpinnings of their panic?

Technical analysis that has little to do with the viability of growth-driving breakthrough technology.

Institutional investors pulling out of private markets? China being a house of cards? Oil? Greece? Technical chart patterns of 1999 showing a run-up that mirrors modern private markets? Food delivery startups being propped up by other startups?

There is no surer sign of the madness of crowds than when investors look to each other rather than fundamentals as they try to divine the true nature of private markets.

Investors who claim to pride themselves on long-term thinking often forget the technological fundamentals that determine long-term viability of companies.

From 2006 to 2011, thousands of professional poker players quit the game, convinced that a certain popular narrative was true: poker had finally become a game of luck.

“When you think of it as a lottery ticket, when you say, ‘This might work, this might not work, I don’t know,’ you’ve already psyched yourself into losing. You’ve talked yourself into not doing as much work. Where we’ve done best over the years is where we had a lot of conviction, where we were willing to put a lot of money into things.”

Weak poker players quit as the bubble popped because they were convinced that poker had become so competitive that it was impossible to have an effective, differentiated strategy.

Poker players who have faith in their own creativity continue to make a living through hard work and study.

In the near future, the antiportfolios of herd-mentality technology investors will swell at unprecedented rates as investors mistakenly look to each other for guidance, rather than looking at the fundamental opportunities afforded by our current technological boom.

Emotional Labor

In 2004 and 2005, college students and well-educated yuppies started playing poker because it was a low-risk, easy way to make money. Wealthy, amateur American poker players were losing money to these college students and yuppies.

There was a huge difference in skill between these two classes of players.

The college students and yuppies read books about statistics, psychology, and complex poker strategy. The wealthy, amateur Americans watched poker on TV and tried to copy what they saw professionals doing on the screen.

For the well-educated college students and yuppies, the only requirement for succeeding at high-stakes poker was patience.

Patience was important because the wealthy, amateur Americans played so poorly that a college student could sit around waiting for opportunities to get money into the pot with a 10:1 advantage.

From 2006 to 2011, legislative and economic circumstances pushed many of the amateur American players out of the game. As the wealthy amateurs disappeared from poker, the high-stakes field became 95% professionals.

In 2005, an average 6-handed online poker table contained 3 professionals and 3 amateurs. In 2006, an average table contained 4 professionals, 1 skilled amateur, and 1 weak amateur. By 2008, most tables were entirely filled with professionals and skilled amateurs.

Weak opponents were nowhere to be found.

In this new world of almost entirely professional poker players, emotional resilience was more important than patience.

Professional players could no longer wait for a clear 10:1 or 5:1 advantage over their opponents. The timid college students and yuppies who maintained a patient, uncreative strategy started to lose money.

Chaotic, hyperaggressive players began to force games in a direction with increased variance, making their opponents call into question their presumed risk-of-ruin. The most extreme example of this was Viktor Blom, a high-stakes player whose willingness to go broke seemed to exceed his fear, leading to a style where he would frequently overbet the pot.

A professional playing against Viktor Blom knew that more money would belost or won in a short time frame than against anyone else.

For Viktor Blom, the primary cost of using this strategy was that emotional control is harder to maintain when you are winning and losing millions of dollars on a more frequent basis than your opponents.

The tradeoff was worth it. Viktor Blom’s brilliant strategy gave him both amathematical advantage and a reputation advantage.

Why is this relevant to software engineering?

Emotional labor is available to all of us, but it is rarely exploited as a competitive advantage.

-Seth Godin

Viktor Blom gained massive competitive advantage by committing emotional labor.

He deliberately played poker in a way that was uncomfortable to everyone at the table, because he judged himself as more capable of dealing with that discomfort than everyone else.

Most software engineers avoid emotional labor.

When software engineers choose to work at a large corporation because it seems luxurious and safe, they are making a mistake. There has never been a better time for engineers to take extreme risks with their careers.

Software engineers are incredibly privileged. Our 9–5 jobs are enjoyable and creative, and many of us have significant free time to do whatever we want. During their free time, software engineers should stretch themselves and exert emotional labor, and see what they are capable of.

In 2005, professional poker players had the option to live a carefree lifestyle. We assumed the gold rush of online poker would never end. Many of us acted irresponsibly with money, as if we would be able to make $30,000 a month for the rest of our lives.

When the poker economy collapsed, many professional poker players’ lives collapsed with it. We had gotten accustomed to The Good Life, but we hadn’t worked hard enough to capitalize fully on the opportunity at hand.

Poker players who worked hard and worked smart during the 2003–2007 boom years were able to survive the bust.

Most poker players did not work hard and smart during the boom.

Most poker players did not practice emotional labor in 2005, when the game was easy. When poker became difficult in 2008, these players were fragile. Most professional poker players were unable to adapt to the newly competitive landscape.

In contrast, Viktor Blom got used to high-risk activity around 2005, shortly after he started to play poker:

After a few weeks of play, Blom90 was regularly playing at $530 sit n gos. After a few more months of play the 15-year-old Viktor Blom had made over $275,000 total at various sites. He then collected all the money onto one site and took on the higher buy-in cash games and sit n gos. This resulted him losing all the money. He then built up a bankroll and deposited $3,000 onto the same site, he took on high buy-in sit’n gos and started to win more and more money. After building his bankroll back up to $50,000 he took on a $310 sit’n go regular and once again lost everything.

Viktor Blom went broke twice as a teenager.

Going broke is not always virtuous. For some poker players, being broke is an addiction. They will make a career out of the manic-depressive cycle of building huge piles of money, only to lose it all.

Viktor Blom became antifragile from his early experiences going broke.

This was long before his winning streak in 2009. When the poker economy collapsed, it didn’t severely affect Viktor Blom because he had been forcefully challenging himself for years before.

In the early days of his career, Viktor relentlessly took risks. The strength of the 2005 poker economy allowed him to rebuild his bankroll each time he went broke.

Software engineers today should be acting like Viktor Blom in 2005.

In 2005, Viktor could lose his entire bankroll playing high stakes, it was easy to rebuild at mid-stakes games. By increasing short-term risk of ruin, he decreased long-term risk of ruin.

In 2016, a software engineer can quit a corporate job and build side projects for 6 months. If none of the side projects turns into a marketable product, that engineer can always go back to the corporation, and can probably ask for a higher salary thanks to the new skills learned from working on those side projects.

Risk taking is an act of emotional labor.

Software engineers can build a product, start a business, write an algorithm, launch a rocket, or program a self-driving car. All of these activities require risk. But many software engineers spend their spare time doing activities with very low risk.

If you commit to being a software engineer who is willing to take risks and commit to emotional labor, you can easily stand out from others.

Build Your Own Ship

I spent my late teenage years playing poker and didn’t write a line of code until my early twenties. Most of the successful engineers I know were coding during their teens.

In order to catch up, I have had to leverage the skills I learned playing poker.

Many new engineers today are faced with the same problem.

You are learning to code as a second career, and it can feel very difficult because it feels like you are throwing away everything from the past and starting from scratch.

Whether you are trained as a barista, a salesperson, or a biologist, you must find skills from your past that you can carry into your career as a software engineer.

A barista is great at sequencing operations that are less trivial than they seem. A salesperson understands how to work with clients and cater to their needs in high-stakes projects. A biologist understands abstractions, and how to think about individual parts of a system in isolation.

Being an outsider is a disadvantage at first, but over time it has tremendous value.

Every job you have had in the past has transferrable skills that can be applied to software engineering. Identifying the advantages you have developed from your past experiences can help you feel more confident.

When you start out as a software engineer, many developers will tell you what to do and how you should act.

These people say: Learn JavaScript. Go to a coding boot camp. Write tests for all your code. Learn to make mobile apps. Use StackOverflow. Learn functional programming. Become a master of the command line.

Every person learns software engineering differently.

Software engineering is an art. To succeed as artists, we have to decide what tools and methodologies we want to use. We have to decide for ourselves.

Poker is also an art. There is no objectively “best” way to play poker. Poker players develop their art form through years of subjective experience.

Haseeb Qureshi described this in “Poker as Shipbuilding”, a section from his masterpiece The Philosophy of Poker:

Imagine that your poker game is a ship, and you, the poker player, are the shipbuilder.

Your ship is not an extension of you. It is not something internal, which exists in your mind. We want to imagine instead that a poker game is an external object — your object, certainly, the product of your craft and hard work, but nevertheless something that exists “out there,” ready to be analyzed, taken apart, and put back together. As a shipbuilder, you have a lot of choices to make on how to craft your ship.

What kind of poker game do you want to build?

You look out into the sea of poker and see hundreds of thousands of ships, all constructed differently, with seemingly varied ideas and intentions behind their construction. Naturally, you only want to choose the best ships to emulate. So you watch videos of the great players, sweat the high stakes games, read well-written articles — and you try to fashion your ship in their likenesses.

But there is a fatal fallacy embedded in this process: no matter how many ships you look at, be it hundreds or thousands, even ships of the finest quality, no amount of studying such ships is going to make you able to build one for yourself. Because looking at ships is a very different process from actually building them. Even if you see a hundred ships which have solved the problem of how to construct a ship, how to keep it upright, how to balance the hull and the mast — you will still have to figure out through building how to solve these problems. You must learn how to build a ship not just in your mind but in your hands — put plank against plank, hammer against nail.

As a poker player, I failed because I copied what I saw other people doing without understanding the reasoning behind it. I did not build my own ship as a poker player.

If your strategy is to copy others, you cannot differentiate yourself from the global talent pool. You cannot differentiate yourself from the machines that are getting smarter every day.

As a software engineer, I try not to make the mistake of blindly copying what is fashionable. A decade ago, I lost most of my money because I was simply following what others were doing.

It is useful to have such a history of pain associated with copying others.

For most people, blindly copying others alleviates pain. When I feel like I am copying others without understanding why, my gut response is to be ashamed and scared of own tendency to replicate.

If you don’t copy the behavior of other engineers, your manager cannot treat you as a highly predictable commodity. You can’t be spun up and assigned to a task like an EC2 cluster.

If you aren’t a highly predictable commodity, you will probably be fired or promoted.

Unfortunately, most companies are not set up to support or encourage entrepreneurial behavior.

Many software engineers end up stuck in jobs that make them unhappy because they simply take orders and do not think through things themselves, considering all their options, and seeing the bigger picture.

Software engineers need to build their own ships.

If your strategy as a software engineer is to only copy what you have already seen, you will follow people into old technologies. You will start companies in crowded markets. You will find yourself surrounded by other people who are afraid to create their own strategies, technologies, and products.

If you build your own ship, the world is full of opportunity.