What’s Behind the Rise of “Challenger Banks”?

Introduction

This Monday, Visa announced a plan to buy fintech startup Plaid at a valuation of $5.3 billion. For a company that, in essence, builds intermediary APIs as a platform for other fintech developers, this was a massive moment and a cap to Plaid’s explosive growth as an independent company. For Visa, which is essentially locked in an oligopoly of scale in credit card processing with Mastercard, this represented a larger bet on the app ecosystem that has grown to depend on Plaid to access financial data in the service of innovation.

Importantly, nearly every company listed on this screen was started in the last ten years. Venture Investment and private capital invested in fintech companies have soared since the Financial Crisis.

It is worth asking, why now? Why have resources and talent flowed towards fintech in the last decade, after the sector arguably lagged behind the explosion of tech startups in other consumer-facing industries? Software Engineering Daily has done several interviews with fintech companies, and with digital banks in particular, that may help answer this question. These companies include Monzo, N26, and NuBank, along with other leaders in the fintech and financial data space including Plaid, Stripe, Green Visor Capital, and several more.

In our interview with Michael Walsh of Green Visor Capital, he laid out three themes that have driven the rise of fintech:

“The tech and AWS is a big piece, regulation was a big piece, and then you have consumer behavior and sentiment.”

Consumer Behavior and Data Access

What is a bank? In our interview with Edward Wible of Nubank, we talked about this very question.

“You may have fin techs that provide know your customer and identity fraud management as a very narrow niche, and that’s a fin tech, but that’s not a bank… the fintech spectrum is very broad and there’s a lot of niches, but the bank is really about the balance sheet and the level of trust and the level of criticality in an economy and the relationship with the regulatory bodies.”

Defining what a bank is and does might seem simple, but consider the graphic below:

This shows the traditional Wells Fargo online banking screen, overlaid with Fintech companies that are building whole businesses around providing the highlighted services. Each of these companies has specialized to provide a service which is offered as part of an aggregated customer experience. Intuition might suggest that a focused, specialized company might outcompete the Wells Fargos of the world attempting to provide a broad menu of services, but Wells Fargo still retains over $1.7 trillion in deposits, compared to just over $1billion for the biggest “challenger bank,” N26.

The term “challenger bank” predates the rise of fintech, and strictly means:

“…a relatively small retail bank set up with the intention of competing for business with large, long-established national banks.”

With the rise of digital banking, the term has come to be used mainly to indicate digital-first banks such as NuBank, N26, Monzo, and others with no or few brick-and-mortar locations, who conduct their business in the cloud and through mobile apps. There are around 40 “challenger banks” in the United States, and more than double that number in the U.K, and many more globally.

The core business of a bank is simple. Richard Dingwell of Monzo told us:

“the classic kind of way for a bank to make money is called net interest margin, which is basically the spread between interest by the bank paid by customers on loans minus the interest paid out by the bank to customers for deposits, which had a credit balance.”

The key to expanding a bank’s business, however, is cross-selling other financial products to their depository customers. All of those services on the Wells Fargo screen are still used widely used; non-interest income accounts for around 42% of Wells Fargo’s revenue and is less vulnerable to cuts in policy rates by the U.S. Federal Reserve. This cross-selling is possible- and profitable, despite the entrance of many new fintech competitors- because Wells Fargo has consumer trust and consumer data.

Well, maybe “trust” is too strong of a word.

At its core, a bank is a data platform that makes money by using its data to accurately calculate risk. Depository banks act as a first point of contact with customers who use debit accounts to store savings, and use the data gained from a long-term relationship with a customer to make loans and cross-sell other financial products. Thomas Philippon of NYU Stern writes:

“The role of the finance industry is to produce, trade and settle financial contracts that can be used to pool funds, share risks, transfer resources, produce information and provide incentives. Financial intermediaries are compensated for providing these services.”

One critical factor in the rise of fintech companies and digital banks has been access to customer data. Before the rise of IT in banking, smaller and startup banks actually had informational advantages over large-scale banks due to their proximity to local communities and customers- data acquired from regular face-to-face interaction and kept in paper records. Since 1990, and especially since the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999, there has been significant concentration in the U.S. banking sector, with the 10 largest Bank Holding Companies accounting for about 70% of the total financial assets, while the number of banks in the United States fell by more than half from 1984 to 2008. Deregulation coincided with the rise of IT in bank infrastructure, which allowed data to be shared across a national and multinational organization.

In our interview with Jean-Denis Graze of Plaid, we spoke about how critical access to data is to a customer’s experience with a bank:

“Most people go to their primary bank to get a loan… That’s what you would do, because that person has the most information. They would give you the best loan. You could try to go to another lender and you’d have to print a bunch of PDFs and go there, but they don’t have a relationship with you. It might be tougher to get the best rate.”

Plaid’s primary business model is to manage the complexity of retrieving bank data and making it available to developers in a standardized set of APIs. The number of banks in developed countries has been dropping since 1990, but there are still over 25,000 banks globally- and most have varying API specifications, legacy systems, or no data access at all. Plaid found value by acting as a middleman, allowing developers to spend more time building their systems and less time wrangling with the complexity of their data sources, leaving more room for innovation.

Regarding the possibilities enabled by greater financial data access, Ben Thompson of Stratechery writes:

“…suddenly consumers could commission robo-advisors to move their cash to whoever is offering the best rates, or to automatically refinance debt. Value-added services from multiple vendors would be equally easy to access, meaning they would have to compete on price or terms. In other words, much like the open Internet, banks fear that profits will be rapidly transformed into consumer benefit.”

Parallel to data services such as Plaid were behavioral shifts in both consumers and banks towards technology and data access. In our interview with Klarna, a digital payments platform in Sweden, Marcus Granstrom told us:

“I think that’s when ecommerce really took off and when people who are perhaps not as tech savvy started using the internet more in my mind at least. So if you talk about the history of Klarna, it basically started with providing a way to pay with invoice in Sweden when we bought online, because people were afraid of handing out their credit card and stuff like that.”

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)’s Oauth2.0 standard, now widely used for authentication and authorization in consumer-facing apps, was released in 2012 and its adoption along with OpenID Connect have helped secure data from the client side, and the influence of Oauth2.0 can be seen on Plaid’s Auth flow as well as both are stateless and limit data access based on a Resource Owner’s choice of grants.

The increase of trust in tech companies to access personal and financial data has corresponded with a drop in trust in traditional banks since the Financial Crisis. In 2018, only thirty percent of Americans reported trust in banks, up from a low of 21% in 2012. The Dodd-Frank Act was passed in the United States in 2010 with the goal to remedy some of the systemic problems in the finance industry that had led to the subprime mortgage crisis and the Great Recession. Among the provisions in the Act were the establishment of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Anti-Predatory Lending Act, both of which seek to impose penalties on banks for misbehavior while leaving room for innovation.

The pullback of large banks from significant segments of the market for loans, particularly for newer borrowers, left space for fintechs with innovative risk assessment algorithms to enter. Given the choice between taking out high-interest payday loans and trusting an app, consumers showed preferences for apps that allowed for differentiation in the market, greater levels of convenience, and higher returns on innovation.

One example of an underserved market. When big banks pulled back from making subprime loans after Dodd-Frank, borrowers in that category shifted to payday loans with interest rates as high as 677%. Fintech lenders able to undercut those prices by better assessing risk had plenty of competitive headroom.

As just one example, Buchak et al. showed that fintech mortgage lenders charged higher rates than traditional lenders, but the higher prices were consistent with 20% faster processing times, indicating that customers were willing to pay more for the convenience. Michael Walsh told us:

“All of a sudden, the biggest lenders to this part of the market have decided to exit that market. There was a necessity for alternative lenders and fintech lenders to fill the gap, and that’s why there was such a big opportunity in lending in 2012-2013, post-financial crisis.”

Underserved markets meant opportunity. Many of the markets that big banks pulled away from were markets with poor access to traditional datasets- typically younger adults with little credit history to build a data set with.Tech-focused financial companies could also collect massive amounts of data to eat into the competitive advantages of large institutions.

Machine learning and Big Data processing frameworks helped better quantify risk and allowed the use of alternative datasets for financial risk assessment, which were exceptionally important for areas of the market that big banks pulled away from. Fintech lenders and banks have led the way with using alternative datasets to assess underwriting risk:

Alternative data for risk assessment has shown promise, but the macroeconomic environment since the Great Recession has been an unusual time due to long-term, suppressed interest rates, leading to possible distortions in the market. Given that, it is always important to investigate the reasons for growing investment in a sector- is it driven by consumer demand or an excess of investor supply? And will the current trends in a unique monetary policy environment continue if rates normalize? A full investigation of this subject is outside the scope of this article, but it’s worth mentioning the case of LendingClub as a caveat to the previous arguments.

Hailed as a fintech success story in the years following the Great Recession, LendingClub faced significant difficulties in 2016 when audits revealed loans were packaged and sold under false pretenses to investors, and that LendingClub had invested company capital in a separate company which bought LendingClub loans. Ben Thompson at Stratechery points out that the subsequent pullback of funding affecting LendingClub’s business model suggested that their market was driven by pressure from suppliers (hedge funds and other large investors) to originate loans rather than by strong consumer demand. Large lenders looking for return in an environment where debt securities were yielding close to zero in real rates went in search of higher-return loans to make, pushing consumer-facing companies to originate more loans- almost an exact mirror of the misaligned incentives in the previous decade’s subprime crisis. The history of the finance industry is filled with examples of companies who claim to have fundamentally altered the risk-return dynamic, from Synthetic CDOs to MBS products in the Savings & Loan Crisis to predatory margin lending in the 1920s. Fintech is not immune to the misalignment of incentives, and it will always be important to be realistic about the effectiveness of technology for risk reduction.

Regulation and Compliance

“…The AWS piece you mentioned was definitely a huge part of it, because building scalable, secure financial services applications historically was unbelievably expensive.”

-Michael Walsh, Green Visor Capital

Since banks handle sensitive customer data, along with people’s savings and livelihoods, significant regulation is in place in nearly every country to oversee the banks’ operations and ensure that customers are protected. Regulation poses a difficulty for startups due to high costs of compliance and rules such as minimum capitalization.

Regulation is both a legal issue and a technological issue- designing secure, fault-tolerant, and compliant systems requires an understanding of the environment in which an application gets used. Raylene Yung of Stripe described in her interview with SE Daily how regulation affects developers and employees at all levels:

“Regulatory concerns, compliance restrictions, they’re just very, very different. Something we’ve seen is in the same way that engineers might have to deeply understand Visa specs. When we enter a new country, we have to really understand what are the requirements there, how do the local payment methods work, what are the different terms and what is the payment experience like for users?”

Traditionally, a company looking to offer services as a bank needed to apply for a banking charter. This process is different in every country, but some features in common to all countries which have adopted the Basel III standards include minimum capitalization, outside audits, retention of deposit insurance, and other costly regulations meant to protect consumers and minimize counterparty risk in the banking system. Some countries have introduced “entry-level charters” to get digital banks to market faster, while others have squashed such efforts.

Fintechs have found several creative ways to get around these regulatory barriers. Each challenger bank that we interviewed made an effort to reach the market during the long process of regulatory approval, typically by working with a third party.

“Before we were allowed to issue our own cards and basically host a bank ourselves, we ran a prepaid program where basically we used an agency and we had our own branded prepaid Mastercard cards where customers could load money and then the app works pretty much the same as the current account app works. So you get sort of full experience and we were able to do iteration and development. But at that time, the system of record for our customers balancers was this third-party card processor system who they had a license before while we were still working on ours.”

Other countries have made efforts to carve out regulatory space for fintech companies. Richard Dingwell also spoke about how the Prudential Regulation Authority in the UK enabled Monzo to get to market quicker:

“When they introduced a new streamlined banking license application process, which is called the mobilization route, and that enables new banks to sort of soft launch in a kind of private stuff only test mode before fully ramping up to accept new customers, and this was done to basically make it easier for new companies and to encourage competition.”

However, government regulation is not the only regulatory barrier to entry for fintech companies, and there are still cases where capital investment in hardware is necessary due to “soft regulations” put in place by payment systems. Companies such as MasterCard enforce policies for companies that partner with them or make use of their services. MasterCard requires specialized hardware in a physical data center for its downstream customers to authorize payments through its network. NuBank, working against time to go to market, worked with a third party that had a working authorizer:

“So we ended up doing an integration with a third-party that already had a working authorizer, and this was, in many ways, a deal with the devil that also saved the company, right?”

-Edward Wible, NuBank

Wible said this was “Something that I don’t regret to this day,” but continued to say that it created a lot of problems getting to scale. We will look at the relationship between technology and scale more closely in the next section.

Ultimately, the combination of an increasingly permissive regulatory environment and a rise in compliant cloud services acting as platforms helped offload complex compliance procedures from developers, making innovation in fintech easier. At the data level, however, the work of guaranteeing bank-quality transaction and account integrity depends on the emergence of cloud services, and new organizational and development philosophies that have arisen to accompany those services.

Cloud Technology Platforms

“Perhaps it doesn’t matter if you miss 20 seconds of a movie, but if you miss 20 seconds of a transaction, it’s a big issue.”

Where is the dividing line between a bank and a technology company? Our early definition of a bank as a data platform does not take care to differentiate banks from tech companies. Everyone might “know a fintech company when they see one,” but what accounts for this?

A “digital bank” is an organization that interfaces with customers like a bank, but operates internally like a tech company. Its processes, technology stacks, and strategies are much more similar to other consumer-tech companies than they are to brick-and-mortar banks with hundreds of thousands of employees worldwide. Tech companies are organized in this way to design for scale- using elements of the tech stack and organizational processes to multiply developer productivity and serve thousands of customers per employee.

“Maybe we need to scale up our AWS build to increase the number of nodes running in a platform, but we don’t need to higher, thousands more employees or build new branches, things like that.”

-Richard Dingwell, Monzo

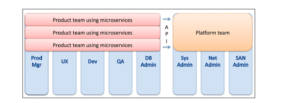

It’s worth taking another look at the Wells Fargo online banking page. Each service here draws from the same dataset- the customer’s history and relationship with the bank- but operates with different logic, in different organizational departments, and with different KPIs and goals. The technology analogue to this loosely coupled collection of business segments is a microservices architecture. The rise in adoption of microservices architecture has been a key factor in the rise of digital banks and fintechs because it is conceptually similar to the “loose coupling” of business services at a traditional bank. Also, adoption of both proprietary and open-source services that help manage the complexity of a microservices architecture has been key to make building a microservices network realistic for smaller startups.

AWS was cited most often by the challenger banks we spoke to as a core technology platform that helped them grow. Richard Dingwall of Monzo told us:

“So I don’t think cloud providers like AWS were a requirement for starting banks like Monzo, but I think there were two really big benefits for companies like us. One was allowing us to do iterative development with our IT infrastructure, kind of in the same way that we do iterative development with our software…If we needed to be kind of provisioning physical hardware changes in our own data center every time our infrastructure changed, the cost would have been much higher and it would have slowed us down a lot.”

As mentioned before, AWS adhering to regulatory standards had trickle-down effects for developers building on it, allowing them to focus on business logic. Even larger organizations like Capital One have benefitted from the robustness of AWS services.

“Capital One announced a partnership with AWS, and how do we use the cloud where anything new that we build we are building on the cloud? We are enabling cloud services for all of our new tech that we’re building and we’re even taking our socalled legacy applications and reengineering them for the cloud. We use a lot of the core AWS services, the storage, the compute services and other tools, like Lambda and RDS.”

-Hillary McTigue

The rise of cloud providers, and managed cloud services, have been instrumental in lowering regulatory barriers to entry. In our conversation with Aparna Sinha, leader of the Product Team for Kubernetes at Google, she described the “second evolution in cloud services.” This is when it became clear that the cloud providers themselves could be as secure as brick-and-mortar competitors, and that their internal compliance with regulations on data security such as ISO 27001 provided trickle-down security benefits to their customers- similar to the notion of “compliance as a service.”

Building one’s cloud architecture with a compliant cloud provider could help smaller companies- especially companies like fintechs competing in a heavily regulated space- to comply with keeping their own data secure.

“So I think actually a lot of the major cloud providers all have all types of compliance certification. So I think this is one of the things where if you talk about R, AWS, or Google Cloud or Azure PCI Compliance, they pretty much all are asking for ISO 27001 certificate. I’m pretty sure most of the cloud vendors would probably have all of those standard ones.”

According to Sinha, the original paradigm shift in cloud services was from “capex to opex”- that is, transforming high-upfront cost capital expenditures on server infrastructure into subscription and usage-based operating services provided by large cloud providers such as AWS. Formerly, huge server costs served as barriers to entry for startups looking to leverage large, fast, and secure datasets to compete with large institutions, but cloud infrastructure helped to break down those barriers.

The Digital Transformation Process

The rise of cloud engineering in the last ten years has not only made it easier to start a compliant, productive, and scalable digital bank; it has also changed the way that developers learn, think, and approach problems. Richard Dingwell of Monzo refers to younger engineers as “children of the cloud,” who have never used bare-metal servers, but have instead spent their careers developing for the cloud. Since those cloud services provide free or trial layers intended for education, the pool of skilled talent with experience building on the cloud from the outset of their career has grown enormously.

With all of these services available, the role of a developer in a modern cloud-first tech company has changed. It is often less costly in terms of labor and time to subscribe to a SaaS vendor or outside service, or to adapt some open source project, than it is to build applications and infrastructure in house. Pat Kua of N26 refers to this transformation as a shift from “makers” to “multipliers”– in essence, breaking down barriers between solutions-focused developers and cost-focused business analysts to find solutions that take both technical specifications and business strategy into account. The cloud environment has given rise to both managed services like AWS and open source projects like Kubernetes that can be integrated as part of a software stack rather than developed internally, freeing up developers to be productive elsewhere.

The question of in-house development versus paying for services is common across all industries, not just finance and fintech. There are many reasons for the consolidation of banks since 1990, but not much evidence that such scale has made those banks more efficient on a cost basis for the consumer. Thomas Phillipon of NYU Stern found that unit costs to the customer of financial intermediation- i.e. acquiring financing, loans, etc, measured based on interest rates and transaction costs- scaled linearly with the quantity of assets under management for financial institutions. In short, this means that core services such as lending did not meaningfully drop in unit cost as the industry grew in size and sophistication.

This growth allowed many of the biggest banks to in-house many of their tech and data operations to the point of creating “walled gardens” of data- at least partially due to regulations around customer privacy. Many large banks still build their technology primarily with proprietary tools; developers at Goldman Sachs, for example, go as far as to use a proprietary trade secret programming language called “Slang” and a 27-year-old database architecture called SecDB.

Now, this is not to suggest that the biggest banks in the world are nearing extinction at the hands of challenger banks- far from it. N26, currently the largest challenger bank, still has a ways to go to match the sheer scale and efficiency-at-scale of the “too big to fail” systemic banks.

Author’s calculations, using $1 billion in deposits versus 1580 employees for N26; $1.3 trillion in deposits versus 250,000 employees for JP Morgan Chase. This is necessarily an imperfect comparison due to different depositor profiles (primarily individuals for N26 versus individuals and businesses for JP Morgan), but a detailed breakdown is beyond the scope of this article.

But larger institutions are making moves indicating that they recognize the advantages of digital banking. Visa’s acquisition of Plaid, mentioned at the beginning of this article, is a great example. Some larger financial companies are engaging in “digital transformations,” which we spoke about with Capital One’s Hillary McTigue.

“I would say that we tend to default to build actually. I mean, we are an engineering technology company and we like to build…However, we’re not going to move forward with a build if there’s a mature tool out there that already meets our needs and does what we need to do and then the cost of building is negated at that point.”

-Hillary McTigue

Organizations with significant legacy code face larger barriers to transformation- whether it be rewriting code, migrating databases, or changing how people work. As Pat Kua of N26 told us,

“So I think banks have been around for quite a while, or little banks have been around for quite a while… are run by mainframe sort of systems built up in maybe the 70s or the 80s. So all the processes and layers of people in terms of how they actually build software or how they run their processes, and it’s very hard to maybe shift all of the organization towards more modern practices, which is what the benefits of newer companies, like Netflix or Uber have and what I feel that we also have because we get to challenge everything from the ground up.”

In his study of business organizations, Stinchcombe wrote that the organizational structure of a business may be an “adaptational” result to the technologies, norms, and competitive environment of the time period that it matures in. A business tends to retain the same basic structure even when the times have changed, barring significant changes to overcome institutional inertia.

Traditional banks may buy fintech startups and add them as part of their larger business, but it is unlikely that JP Morgan Chase will shift to being a “developer-centric” company like these challenger banks in response to a changing financial technology environment, despite the advantages of new technologies and business strategy. It should also be noted that the same regulatory framework that has made large banks pull back from sections of the market also provides guarantees to the “Systemically Important Financial Institutions”- SIFIs- against failure or losses, meaning that the financial giants will likely stay around even if they are outcompeted.

“You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to know that you should use modern open source technology and that you should write tests, and that you should kind of maintain and look out for the maintenance and technical data of your stack, right? It’s easy to talk about it. It’s actually really hard to have the discipline to do it and to do it consistently over a period of years. So I expect execution to really be the differentiator.”

-Edward Wible, Nubank

But the rise of challenger banks and the diversification of the fintech ecosystem over the last decade marks a significant shift in the way we think about our personal finances. This shift was enabled by changes in consumer behavior, regulatory changes, and the rise of cloud technologies- and further innovations will undoubtedly provide for an entirely new generation of digital banking and finance platforms in the coming decade. Given their fluency with cloud technology, their strong growth, and their competitive agility, challenger “digital-first” banks appear well-positioned to capitalize on the coming change.